Canadian

Research

Alberta

British

Columbia

Manitoba

New Brunswick

Newfoundland

Northern

Territories

Nova Scotia

Nunavut

Ontario

Prince Edward

Island

Quebec

Saskatchewan

Yukon

Canadian Indian

Tribes

Chronicles of

Canada

Free Genealogy Forms

Family Tree

Chart

Research

Calendar

Research Extract

Free Census

Forms

Correspondence Record

Family Group Chart

Source

Summary New Genealogy Data

Family Tree Search

Biographies

Genealogy Books For Sale

Indian Mythology

US Genealogy

Other Websites

British Isles Genealogy

Australian Genealogy

FREE Web Site Hosting at

Canadian Genealogy

|

Red River and Pembina

Scarcely had the settlers taken stock of their

surroundings on the Red River when they were chilled to the marrow

with a sudden terror. Towards them came racing on horse-back a

formidable-looking troop, decked out in all the accoutrements of the

Indian,, spreading feather, dangling tomahawk, and a thick coat of

war-paint. To the newcomers it was a never-to-be-forgotten

spectacle. But when the riders came within close range, shouting and

gesticulating, it was seen that they wore borrowed apparel, and that

their speech was a medley of French and Indian dialects. They were a

troop of Bois Brűlés, Metis, or half-breeds of French and Indian

blood, aping for the time the manners of their mothers' people.

Their object was to tell Lord Selkirk's party that settlers were not

wanted on the Red River; that it was the country of the fur traders,

and that settlers must go farther afield.

This was surely an inhospitable reception, after a long and

fatiguing journey. Plainly the Nor'westers were at it again, trying

now to frighten the colonists away, as they had tried before to keep

them from coming. These mounted half-breeds were a deputation from

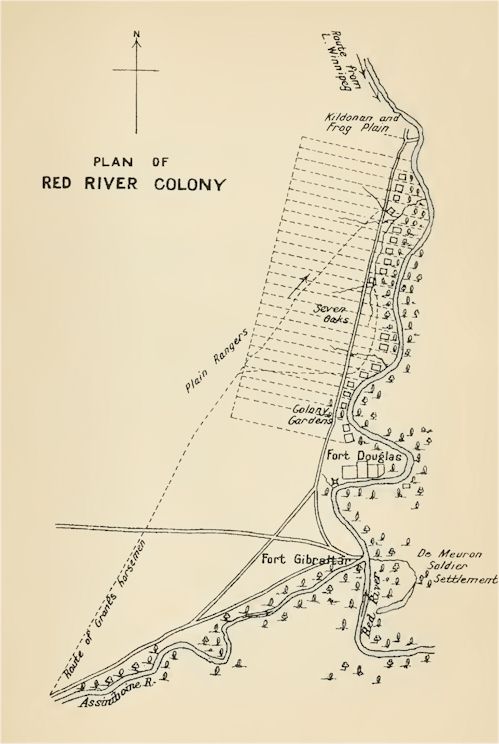

Fort Gibraltar, the Nor'westers' nearest trading-post, which stood

two miles higher up at 'the Forks,' where the Red River is joined by

the Assiniboine.

Nevertheless, Governor Macdonell, having planned as dignified a

ceremony as the circum-stances would allow, sent to the Nor'westers

at Fort Gibraltar an invitation to be present at the official

inauguration of Lord Selkirk's colony. At the appointed hour, on

September 4, several traders from the fort, together with a few

French Canadians and Indians, put in an appearance. In the presence

of this odd company Governor Macdonell read the Earl of Selkirk's

patent to Assiniboia. About him was drawn up a guard of honor, and

overhead the British ensign fluttered in the breeze. Six small

swivel-guns, which had been brought with the colonists, belched

forth a salute to mark the occasion. The Nor'westers were visibly

impressed by this show of authority and power. In pretended

friendship they entered Governor Macdonell's tent and accepted his

hospitality before departing. At variance with the scowls of trapper

and trader towards the settlers was the attitude of the full-blooded

Indians who were camping along the Red River. From the outset these

red-skins were friendly, and their conduct was soon to stand the

settlers in good stead.

The provisions brought from Hudson Bay were fast diminishing and

would soon be at an end. True, the Nor'westers offered for sale

supplies of oats, barley, poultry, and the like, but their prices

were high and the settlers had not the means of purchase. But there

was other food. Myriads of buffalo roamed over the Great Plains.

Herds of these animals often darkened the horizon like a slowly

moving cloud. In summer they might be seen crop-ping the prairie

grass, or plunging and rolling about in muddy 'wallows.' In winter

they moved to higher levels, where lay less snow to be removed from

the dried grass which they devoured. At that season those who needed

to hunt the buffalo for food must follow them wherever they went.

This was now the plight of the settlers: winter was coming on and

food was already scarce. The settlers must seek out the winter

haunts of the buffalo.

The Indians were of great service, for they offered to act as

guides.

A party to hunt the buffalo was organized. Like a train of pilgrims,

the majority of the colonists now set out afoot. Their dark-skinned

escort, mounted on wiry ponies, bent their course in a southerly

direction. The redskins eyed with amusement the queer-clad strangers

whom they were guiding. These were ignorant of the ways of the wild

prairie country and badly equipped to face its difficulties.

Sometimes the Indians indulged in horse-play, and a few of them were

unable to keep their hands off the settlers' possessions. One

Highlander lost an ancient musket which he treasured. A wedding ring

was taken by an Indian guide from the hand of one of the women. Five

days of straggling march brought the party to a wide plateau where

the Indians said that the buffalo were accustomed to pasture. Here

the party halted, at the junction of the Red and Pembina rivers, and

awaited the arrival of Captain Macdonell, who came up next day on

horseback with three others of his party.

Temporary tents and cabins were erected, and steps were taken to

provide more commodious shelters. But this second winter threatened

to be almost as uncomfortable as the first had been on Hudson Bay.

Captain Macdonell selected a suitable place south of the Pembina

River, and on this site a store-house and other buildings were put

up. The end of the year saw a neat little encampment, surrounded by

palisades, where before had been nothing but unbroken prairie. As a

finishing touch, a flagstaff was raised within the stockade, and in

honor of one of Lord Selkirk's titles the name Fort Daer was given

to the whole. In the meantime a body of seventeen Irishmen, led by

Owen Keveny, had arrived from the old country, having accomplished

the feat of making their way across the ocean to Hudson Bay and up

to the settlement during the single season of 1812. This additional

force was housed at once in Fort Daer along with the rest. Until

spring opened, buffalo meat was to be had in plenty, the Indians

bringing in quantities of it for a slight reward. So unconscious

were the buffalo of danger that they came up to the very palisades,

giving the settlers an excellent view of their drab-brown backs and

fluffy, curling manes.

On the departure of the herds in the spring-time there was no reason

why the colonists should remain any

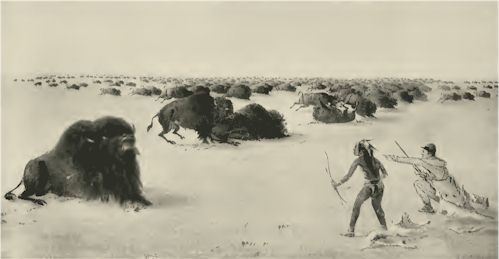

Hunting the Buffalo

From a painting by George Catlin

longer at Fort Daer. Accordingly the entire band plodded wearily

back to the ground which they had vacated above 'the Forks ' on the Red River.

As the season of 1813 advanced, more solid structures were erected on this site,

and the place became known as Colony Gardens. An attempt was now made to prepare

the soil and to sow some seed, but it was a difficult task, as the only

agricultural implement possessed by the settlers was the hoe. They next turned

to the river in search of food, only to find it almost empty of fish. Even the

bushes, upon which clusters of wild berries ought to have been found, were

practically devoid of fruit. Nature seemed to have veiled her countenance from

the hapless settlers, and to be mocking their most steadfast efforts. In their

dire need they were driven to use weeds for food. An indigenous plant called the

prairie apple grew in abundance, and the leaves of a species of the goosefoot

family were found to be nourishing.

With the coming of autumn 1813 the experiences of the previous year were

repeated. Once more they went over the dreary road to Fort Daer. Then followed

the most cruel winter that the settlers had yet endured. The snow fell thickly

and lay in heavy drifts, and the buffalo with animal foresight had wandered to

other fields. The Nor'westers sold the colonists a few provisions, but were

egging on their allies, the Bois Brűles, who occupied a small post in the

vicinity of the Pembina, to annoy them whenever possible. It required courage of

the highest order on the part of the colonists to battle through the winter.

They were in extreme poverty, and in many cases their frost-bitten, starved

bodies were wrapped only in rags before spring came. Those who still had their

plaids, or other presentable garments, were prepared to part with them for a

morsel of food. With the coming of spring once more, the party travelled

north-ward to 'the Forks ' of the Red River, re-solved never again to set foot

within the gates of Fort Daer.

Meanwhile, some news of the desperate state of affairs on the Red River had

reached the Earl of Selkirk in Scotland. So many were the discouragements that

one might for-give him if at this juncture he had flung his colonizing scheme to

the winds as a lost venture. The lord of St Mary's Isle did not, however,

abandon hope; he was a persistent man and not easily turned aside from his

purpose. Now he went in person to the straths and glens of Sutherlandshire to

recruit more settlers. For several years the crofters in this section of the

Highlands had been ejected in ruthless fashion from their holdings. Those who

aimed to 'quench the smoke of cottage fires' had sent a regiment of soldiers

into this shire to cow the Highlanders into submission. Lord Selkirk came at a

critical moment and extended a helping hand to the outcasts. A large company

agreed to join the colony of Assiniboia, and under Selkirk's own superintendence

they were equipped for the jour-ney. As the sad-eyed exiles were about to leave

the port of Helmsdale, the earl passed among them, dispensing words of comfort

and of cheer.

This contingent numbered ninety-seven per-sons. The vessel carrying them from

Helms-dale reached the Prince of Wales of the Hudson's Bay Company, on which

they embarked, at Stromness in the Orkneys. The parish of Kildonan, in

Sutherlandshire, had the largest representation among these emigrants. Names

commonly met with on the ship's register were Gunn, Matheson, MacBeth,

Sutherland, and Bannerman.

After the Prince of Wales had put to sea, fever broke out on board, and the

contagion quickly spread among the passengers. Many of them died. They had

escaped from beggary on shore only to perish at sea and to be consigned to a

watery grave. The vessel reached Hudson Bay in good time, but for some un-known

reason the captain put into Churchill, over a hundred miles north of York

Factory. This meant that the newcomers must camp on the Churchill for the

winter; there was nothing else to be done. Fortunately partridge were numerous

in the neighborhood of their encampment, and, as the uneventful months dragged

by, the settlers had an unstinted supply of fresh food. In April 1814 forty-one

members of the party, about half of whom were women, undertook to walk over the

snow to York Factory. The men drew the sledges on which their provisions were

loaded and went in advance, clearing the way for the women. In the midst of the

company strode a solemn-visaged piper. At one moment, as a dirge wailed forth,

the spirits of the people drooped and they felt themselves beaten and forsaken.

But anon the music changed. Up through the scrubby pine and over the mantle of

snow rang the skirl of the undefeated; and as they heard the gathering song of

Bonnie Dundee or the summons to fight for Royal Charlie, they pressed forward

with unfaltering steps.

This advance party came to York Factory, and, continuing the

journey, reached Colony Gardens without misadventure early in the summer. They

were better husbandmen than their predecessors, and they quickly addressed

themselves to the cultivation of the soil. Thirty or forty bushels of potatoes

were planted in the black loam of the prairie. These yielded a substantial

increase. The thrifty Sutherlanders might have saved the tottering colony, had

not Governor Macdonell committed an act which, however legally right, was

nothing less than foolhardy in the circumstances, and which brought disaster in

its train.

In his administration of the affairs of the colony Macdonell had shown good

executive ability and a willingness to endure every trial that his followers

endured. Towards the Nor'westers, however, he was inclined to be stubborn and

arrogant. He was convinced that he must adopt stringent measures against them.

He determined to assert his authority as governor of the colony under Lord

Selkirk's patent. Undoubtedly Macdonell had reason to be indignant at the

unfriendly attitude of the fur traders; yet, so far, this had merely taken the

form of petty annoyance, and might have been met by good nature and diplomacy.

In January 1814 Governor Macdonell issued a proclamation pronouncing it unlawful

for any person who dealt in furs to remove from the colony of Assiniboia

supplies of flesh, fish, grain, or vegetable. Punishment would be meted out to

those who offended against this official order. The aim of Macdonell was to keep

a supply of food in the colony for the support of the new settlers. He was,

however, offering a challenge to the fur traders, for his policy meant in effect

that these had no right in Assiniboia that it was to be kept for the use of

settlers alone. Such a mandate could not fail to rouse intense hostility among

the traders, whose doctrine was the very opposite. The Nor'westers were quick to

seize the occasion to strike at the struggling colony.

Red River Colony

This site includes some historical materials that

may imply negative stereotypes reflecting the culture or language of

a particular period or place. These items are presented as part of

the historical record and should not be interpreted to mean that the

WebMasters in any way endorse the stereotypes implied.

The Red River Colony, A Chronicle of the

Beginnings of Manitoba, By Louis Aubrey Wood, Toronto, Glasgow,

Brook & Company 1915

Chronicles of Canada |